Only the street sign remains: where Lappe Lane used to end at Shirls Street, Spring Hill

Lappe Lane is one of the more fascinating throughways you’re likely to travel. Roughly equal parts city steps, paved road, and (non-existent) “paper street,” Lappe begins down in Spring Garden and then runs straight up and over the hill, back down the other side, through a cemetery (though you wouldn’t know it), and just keeps going.

If you like hiking the steps, there’s a decent chance you’ve already climbed Lappe Lane’s lower flights where the stairs intersect Spring Garden Ave. or Goehring Street and continue up to Yetta and St. John’s Cemetery at the top of the hill. These early sections offer great options to what entry-level step trekkers are after–steep vertical ascents, great city views, kooky between-house catwalks, and lots of nice here-to-theres with alternate options to get back down the hill.

Even so, you’ve probably never made it up here, where we are, at the very end. And that’s because–like some twisted Zen koan–even where Lappe Lane finally ends, it doesn’t actually go there.

Lappe Lane, from South Side Ave. to Fabyan Street, Spring Hill

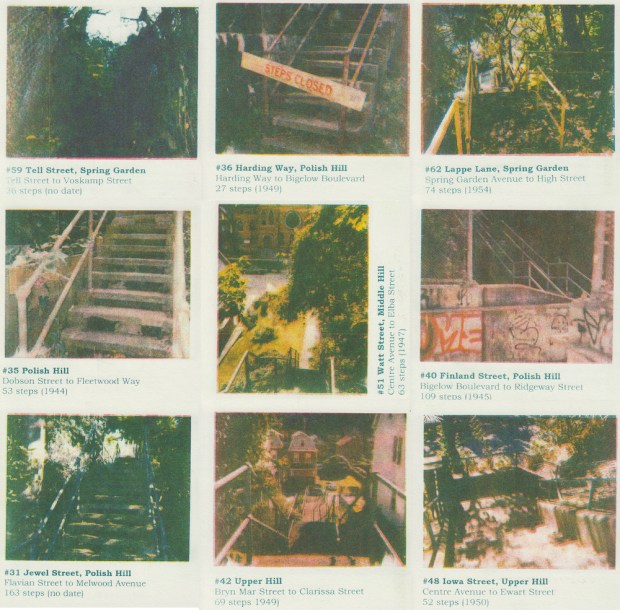

Laura Zurowski has an ambitious goal: visit and document every one of Pittsburgh’s seven hundred and thirty-nine (known) sets of public steps. As if all the navigating, stair-climbing, and list-checking-off weren’t enough, Zurowski’s Mis.Steps project gets even more complicated. No mere exercise/sight-seeing venture, each and every steps visit is followed by an additional mixed media exploration via old-school/pre-digital instant photography, short prose, colored sidewalk chalk, print-making, and final distribution via the computer Internet.

We’ll get to all this. Today, though, we’re just trying to locate the very last two flights of Lappe Lane, at the far north end of Spring Hill.

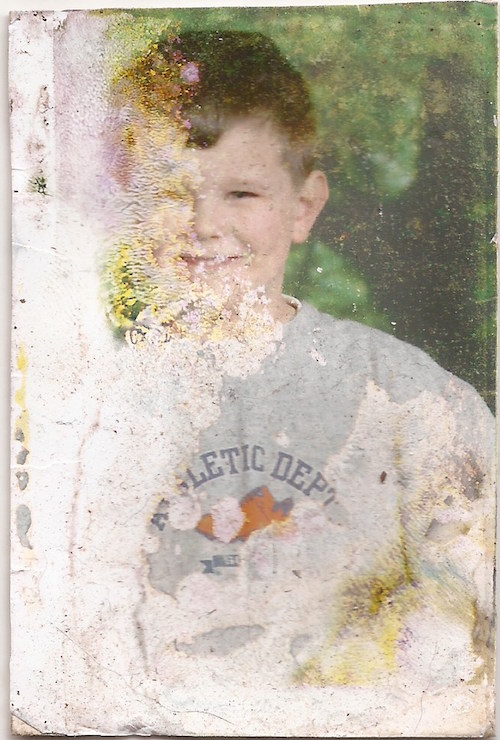

In the weeds: Laura Zurowski with her Polaroid Spectra 2 camera

“Pittsburgh chose me,” Zurowski says of her relocation from Providence, by-way-of upstate New York. The decision came six years ago alongside the desire to own a home in a place she could pursue more creative projects. “I asked myself, ‘What do I want life to be?’ and the answer was that I wanted to be open to ideas; to have a more robust, creative existence.”

The interest in the city steps only came some time after the move. Seeing the volume of empty houses in Pittsburgh was new, startling, and inspirational–but also melancholy. “Every one of those (abandoned) homes contained people’s lives, so seeing them empty is really sad,” Zurowski says, “With the steps–even if they’re in bad condition–I never feel sad like I do with empty houses.”

That, coupled with Bob Regan’s Orbit essential The Steps of Pittsburgh: Portrait of a City (The Local History Company, 2004) was enough to send Zurowski on her mission.

Chalk it up: Zurowski tags another completed set of steps with a Polaroid-sized chalk square.

We see one small boarded-up home, but for the most part, the houses on this block all appear both lived-in and loved. Lappe Lane’s thirty-or-so steps starting from South Side Ave. [Mis.Steps Trip #109] are easy enough to spot. There is no street sign at this intersection, but a familiar pair of red-brown handrails reaches out of the hillside and right down to the edge of the quiet residential road.

But try walking up these stairs and you’re quickly ensnared in wild jumble of weedy overgrowth, thorny bramble, and whatever those plants are that leave prickly stickers on your socks and pant legs. Even half-way up the short flight, it’s obvious you’ll not be going far. One of the uphill homeowners has–perhaps, illegally–built an elaborate A-frame treehouse directly blocking the public right-of-way. Even if someone wanted to, no one’s going anywhere on these steps.

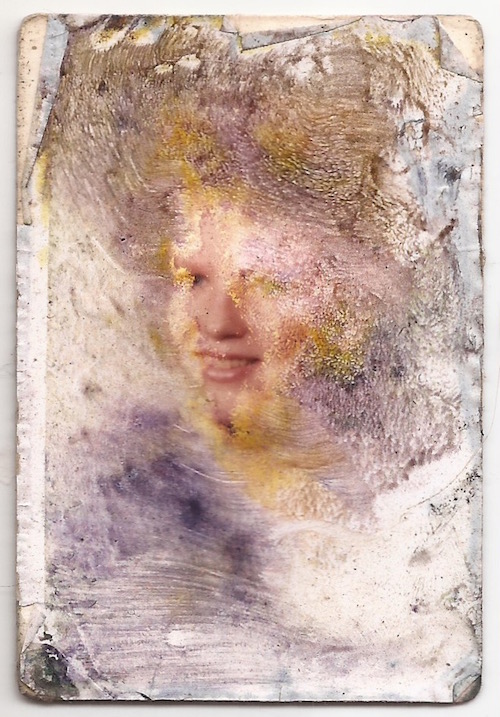

Trip #109: Lappe Lane – S. Side Ave. Polaroid [photo: Laura Zurowski]

Zurowski fights her way through the thicket of tall grass, up past the first plateau, and on until nearly swallowed by the plant kingdom. There’s a shrugged acceptance this is far as these particular steps will allow, an untangling from the jaggers, careful descent back to the landing, and then hands dart into the backpack for the Polaroid camera. The single picture–there is only one per set of steps–is taken in an instant.

“My friend who’s a photographer said, ‘You’re going to have a really hard time coming up with 739 ways to take pictures of stairs’,” Zurowski says, “And it would be hard if they were all the same–but I haven’t come across two sets that look alike.”

“I look at the Polaroid [photos] like they’re portraits of people,” Zurowski continues, “If I were going to give human-like qualities to the steps, what would they be like? Hopefully the Polaroid captures the essence of what each flight of steps is all about.”

Late summer scene: Polaroid from Trip #61 – Harpster Street, Oct. 2017, Troy Hill [photo: Laura Zurowski]

The instant photograph is ejected from the camera, rested on a stair tread, and then the journals come out. There are two of them: one for “field notes”; the other, narrative impressions. With each visit, Zurowski includes a short meditation on the scene, which will be used later on.

Zurowski scratches a rough square, just about the size of a Polaroid picture, with sidewalk chalk on one of the stair risers. Mis.Steps super fans are undoubtedly taking selfies with chalk squares around town right now. Finally, the iPhone is used to snap one last picture summing up the whole scene.

With that, we’re on to Trip #110–the very end of Lappe Lane, just up the hill from where we are now. Here, Zurowski will do it all over again, but, just like every other one of those 739 sets of steps, this one is completely different from the one we just saw. For one, there aren’t any steps here (anymore).

A blast of autumn past: Mis.Steps summary photo (including Polaroid and chalk square) from Trip #68 – Basin Street, Troy Hill/Spring Garden, Oct. 2017 [photo: Laura Zurowski]

That’s a lot of process–but it ain’t over yet! Back home, Zurowski completes the cycle with the publishing of each Mis.Steps adventure every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. The narrative is honed, the Polaroid digitized, and the pairing of image + words goes out to the world via the Mis.Steps’

blog,

Instagram, and

Craig’s List “Missed Connections” page. That’s right: between “Kinky Dom Roleplay – m4m (Canonsburg)” and “Thanks for the hot time – m4m (McKeesport)” there’s a little

story and photo about listening to birdsongs on the Morningside Avenue steps.

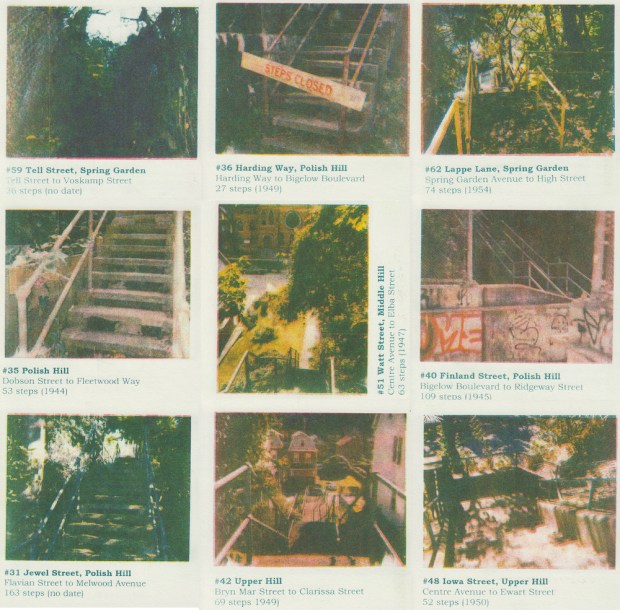

#20 Diulius Way, Central Oakland. Risograph print by Jimmy Riordan.

I know what you’re thinking: All this sounds great, but there’s nothing to hang on my wall or swap with friends! That’s where you’re sorely mistaken. Conveniently, Mis.Steps has taken the whole project out of the aether and fed it through a 1980s-era technology at the hands of Braddock printer Jimmy Riordan.

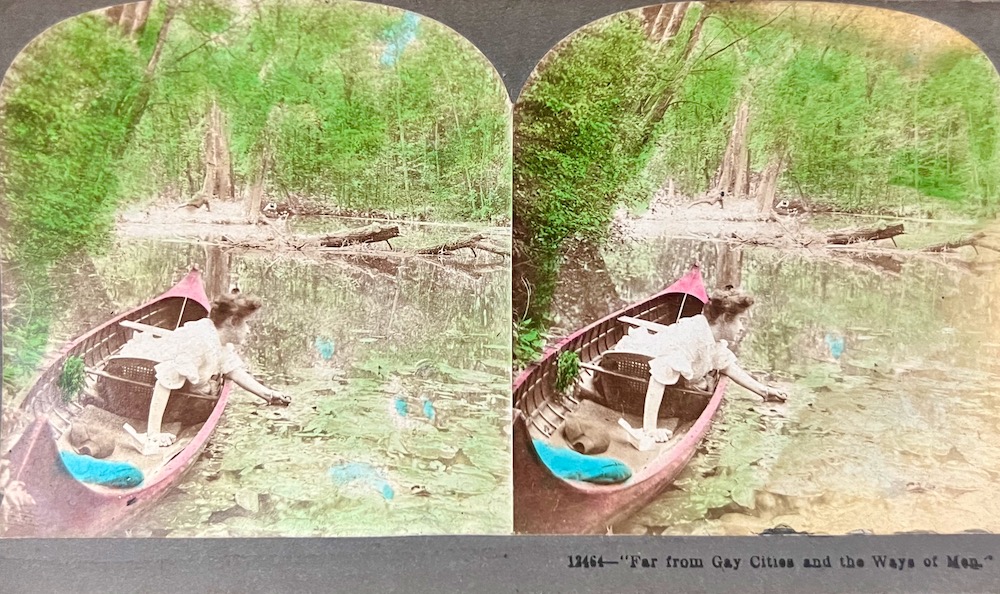

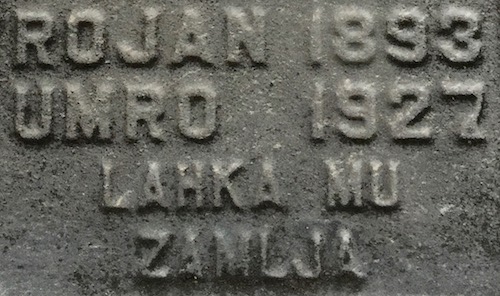

The result is a hard copy series of “trading cards” that further abstract the original murky Polaroid into ghostly, high-contrast 3-color art prints. In addition to the photographic image, the cards contain the Mis.Steps index number, street and neighborhood names, location, step count, and the city’s construction date (if known) on the front and the narrative text on the back. Card collections are available from the Mis.Steps website and Copacetic Comics in Polish Hill.

No two alike: various Mis.Steps Polaroid-sized Risograph trading cards printed by Jimmy Riordan

If it’s not obvious yet, Laura Zurowski really loves Pittsburgh’s city steps–Orbit readers know we share an opinion on this matter. “If there’s an underlying goal,” Zurowski says of the Mis.Steps project, “It’s to get people to visit the stairs. I’d like to encourage people to look around, to check out other parts of the city, and to become connected with their neighborhoods.” We couldn’t agree more.

Route with a view: Zurowski at the top of the Vinial Street steps, part of the “Spring Garden Stair Stepping” event, Troy Hill

Still not enough Mis.Steps for you? Well, you’re in luck. Zurowski has teamed up with Threadbare Cider for a series of combined guided city step hikes and cider house tours/tastings dubbed Spring Garden Stair Stepping (and Cider Sipping). You’re probably too late for today’s kick off hike–and it sold out way ahead of time anyway–but there will be a couple more chances with repeat events April 15 and May 20.