unknown

The first thing you’ll notice are the names: Kolesar, Zgurich, Csajka, Lippl, Knezevic. Any cemetery in Pittsburgh–certainly any older cemetery associated with a Catholic parish–will have its share of Eastern Europeans as long-term residents, but this one’s different.

Sure, there’s a couple token Irish and Italian names loitering among the stones–we spotted a Finnegan, a DiBlasio, and an Andreucci–but you’ll not any find any Smith, Jones, Williams, or Davis buried here. Kusmircak, Blosl, Czegan, Fabijanec, and Kuchta are the rule, not the exception.

unknown

unknown

Loretto Cemetery rests at the very easternmost end of the big mount that rises above the South Side. Far below, but difficult to see from the steep angle, is an S-shaped crook in the Monongahela as it snakes between Hazelwood and the South Side. It’s an enviable location: quiet, vacant, and with terrific long views across the river to Oakland and Greenfield on the other side.

We hadn’t come here looking for the dead, but any new cemetery is worth a poke-see when you trip across it. When we did, those names–Cvetkovic, Vnencsak, Mlinac, Turkovich, Opacic–just popped right out like candy on the shelf. Something interesting would surely await.

Toni Poljak

unknown

That something came in the form of a small black-and-white photograph, cast onto an oval-shaped ceramic disc and inset directly into one of the tower-like headstones. The posed portrait was of a middle-aged woman, “Mother” Antonija Komlenić, Victorian in both high-necked formal dress and dour, no-fun-allowed expression.

The colored mortar used to anchor the piece in stone is half chipped-away, eroded by a century of industrial mill exhaust and harsh Western Pennsylvania weather[1]. The image is all there, but it’s faded and scored by sharp cracks awkwardly bisecting Komlenić’s face and torso.

Antonija Komlenić

Antonija Komlenić (detail)

Looking around a little closer now, another headstone is embedded with the same kind of oval-shaped photo just steps away. This one features a large man in suit and tie, his head is cocked and he wears a kind of bushy mustache that hasn’t been in vogue for a very long time. Both the deep black of his dress jacket and the shade of the photo’s backdrop have worn away significantly. There’s an angled crack through the ceramic just under the deceased’s chin suggesting a sinister garrote, but the man’s face is calm–bored, even–and remarkably untouched by the hands of time.

Suddenly aware and on the lookout for more, the grave photos are all over–on stones tall and thin, mounted below marble crosses and flat on granite. There may be a couple dozen in total, scattered across the sections closest to Loretto’s entry gate on Devlin Street. At least as many feature an empty cutaway in the stone where the inset image is no longer present; its former tenant stolen or broken, weathered or vandalized long ago.

unknown

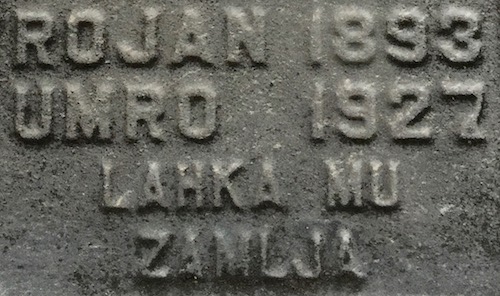

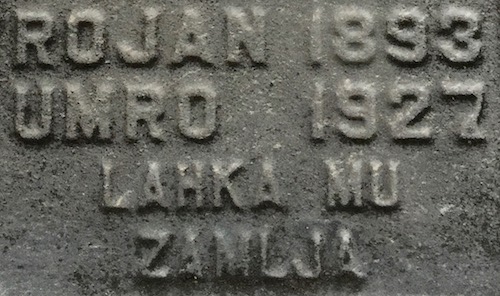

Lahka mu Zamlja

Lahka Mu Zamlja (alternately Laka Mu Zemlja), the Internet informs us, is either a Serbian or Croatian (perhaps both?) expression of condolence that translates to “may the black earth be easy on him.” Confirming this with Google translate was not very successful–it came up with preposterous gropes in the dark such as “easy land of mu” or “light mu country”[2]. But as this is likely an arcane idiom, it seems a pretty safe Balkanization of Rest in Peace.

We found this phrase on quite a number of Loretto’s graves, including some of the very ones with the inset portraits. While it’s impossible to know how “easy” the black earth was on each of these folks, the atmosphere above ground has taken varying degrees of torture out on their memorials. The photos here labeled unknown aren’t for lack of note-taking–there simply isn’t any text still readable on the headstones.

unknown

unknown

The Orbit has spent considerable time in a whole lot of bone yards over the years and we’ve written quite a bit on the subject already. It’s nothing special to see more recent headstones with all manner of high-tech integral photos, bas reliefs, and digital engravings of the deceased, his or her family, loved ones, hobbies, and The Pittsburgh Steelers. But these hundred-year-old…ish[3] photographs-turned-grave ornaments are new to this blogger. Even if I have encountered other late Victorian/pre-war ceramic photos on headstones before, it certainly wasn’t with the quantity or density found in Loretto.

They’re something special, for sure. For one, simply because of the number that are still here [and that’s even more remarkable by the obvious number that are not]. More than that, though, it may be the context or the unpredictable deterioration they’ve been through, but the people in these photos seem to look right through you with a dark, foreboding wisdom of time and fate.

Old photos are almost always interesting. In these, though, there’s somehow a deeper presence. “Wife” Maria Miklin died in 1941, but her sepia-toned portrait as a young woman–scored, chipped, and cracked across the face and torso–seems to defiantly say is that all you got? Just wait ’til you get here, Jack. Lahka Mu Zamlja, indeed.

Maria Miklin

unknown

If existential blogging is what you’re looking for, The Orbit is qualified to satisfy. This whole bag conjured up all kinds of deep thoughts on memory and preservation and forever–luckily, we’ve also got a bunch more interesting photos to back that up. We’ll get to all that in Part 2.

GETTING THERE: Loretto Cemetery is in Arlington Heights and can be reached by going all the way to the east end of Arlington Ave. until it curls around to become Devlin Street. If you want a great hike, though, The Orbit recommends starting on the South Side at the base of the Oakley Way steps and making the journey all the way up and over on foot.

[1] In this case, literally a century; Antonija Komlenić died exactly one hundred years ago, in 1916.

[2] Note to Google: when you get tired of mucking about with driverless cars, see if you can translate “mu” from Croatian!

[3] An incredible number of these headstones have no remaining legible text, but the ones that do date from the 1910s to 1940s.